Game Maps

Whether alone or in teams, for pleasure or profit, sporting or seated, games have been an ever-present feature of every civilization. With multiple participants vying to achieve a goal by following a set of rules, games provide an outlet for the natural human instinct for competition without the risk incurred in, for example, battle. Indeed throughout history, many games have served as a microcosm of war, whether that involves taking down one’s opponent’s king, as in chess, taking turns to attack and defend, seen in all sorts of games from rugby to bridge, or racing to a certain destination, be it on foot or with a counter.

The latter has proved most prolific in the form of board games, which are often based around the competition to reach a final goal by following a designated route. This is a clear simulation of the common real-life objective of moving through space to get to a determined location, and it is therefore no surprise that some of the earliest producers of modern board games were also mapmakers.

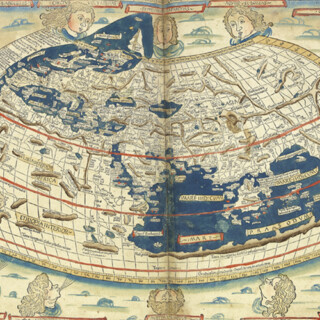

The most fundamental aim of cartography is to create an accessible representation of reality that allows people to locate things and to get from one place to another. Maps are also, however, objects of art, entertainment and education. All of these aspects converge in the game map, which first appeared at a time of significant expansion in each of these areas.

During the eighteenth century, not only were industrial advances making large-scale printing easier, but they were also generating something that had never before been available to the majority of society: leisure time. Paired with growing literacy rates across society and greater understanding of the importance of childhood education, this gave birth to a wave of new and unique games, in the form of jigsaw puzzles, playing cards, and board games.

In fact, the first jigsaws were created from dissected maps which had to be rearranged by the player to form the world, continent or country shown. Their invention has commonly been attributed to John Spilsbury, a British cartographer, engraver and map-seller who affixed maps to a wooden board and carved out each country (Item 1). Earlier references, however, suggest that these sorts of geographical games were already being made by a Madame de Beaumont in the mid-seventeenth century.

Both Beaumont and Spilsbury’s sets were luxurious commodities and thus popular among the elite, for whom such items became symbols of status. In Jane Austen’s 1814 novel ‘Mansfield Park’, for example, the poor protagonist is mocked by her wealthy cousins because she “cannot put the map of Europe together”. The growth of mass education and reduction in printing costs during the nineteenth century, however, meant that these sorts of educational materials became more commercially available and accessible to a wider range of children. Spilsbury’s puzzles, which are described in Mortimer’s Universal Director for 1763 as tools ‘to facilitate the Teaching of Geography’, present a wealth of geographical information, including important cities, rivers and bodies of water, which would certainly have helped augment any child’s knowledge of the world.

In fact, the first jigsaws were created from dissected maps which had to be rearranged by the player to form the world, continent or country shown. Their invention has commonly been attributed to John Spilsbury, a British cartographer, engraver and map-seller who affixed maps to a wooden board and carved out each country (Item 1). Earlier references, however, suggest that these sorts of geographical games were already being made by a Madame de Beaumont in the mid-seventeenth century.

Both Beaumont and Spilsbury’s sets were luxurious commodities and thus popular among the elite, for whom such items became symbols of status. In Jane Austen’s 1814 novel ‘Mansfield Park’, for example, the poor protagonist is mocked by her wealthy cousins because she “cannot put the map of Europe together”. The growth of mass education and reduction in printing costs during the nineteenth century, however, meant that these sorts of educational materials became more commercially available and accessible to a wider range of children. Spilsbury’s puzzles, which are described in Mortimer’s Universal Director for 1763 as tools ‘to facilitate the Teaching of Geography’, present a wealth of geographical information, including important cities, rivers and bodies of water, which would certainly have helped augment any child’s knowledge of the world.

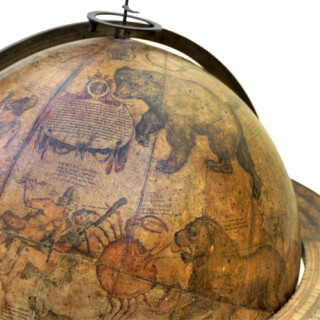

Some publishers took cartographical puzzles to the next level by creating 3D jigsaws out of globes. One such puzzle globe (Item 3) was produced in 1867 by Alphonse Giroux, a French artist who had trained under Jacques-Louis David and had later established a paint shop. Displaying cartography from several decades earlier, Giroux’s globe was dissected into eight cross-sections showing continental maps on the upper side and providing illustrated information on the reverse. Each cross-section was itself divided into four or six pieces, which then had to be assembled to form the globe. Similar puzzle globes were being produced in London at the same time, but no doubt because of their technicality and expense, they are much rarer than their two-dimensional counterparts.

Some publishers took cartographical puzzles to the next level by creating 3D jigsaws out of globes. One such puzzle globe (Item 3) was produced in 1867 by Alphonse Giroux, a French artist who had trained under Jacques-Louis David and had later established a paint shop. Displaying cartography from several decades earlier, Giroux’s globe was dissected into eight cross-sections showing continental maps on the upper side and providing illustrated information on the reverse. Each cross-section was itself divided into four or six pieces, which then had to be assembled to form the globe. Similar puzzle globes were being produced in London at the same time, but no doubt because of their technicality and expense, they are much rarer than their two-dimensional counterparts.

Many of the earliest printed commercial playing cards were also produced by mapmakers, and some even bore cartographical designs. The card, which shares its name with the word for map in several languages (carte, Karte), has also been ubiquitous across time and space; played by nomads and emperors, parlour maids and Lords, the deck represents a shared pastime that connects all levels of society across the ages.

From the sixteenth century onwards, mapsellers such as John Seller, Richard Blome and Thomas Bowles of London, Pieter Schenck of Leipzig, and Pieter Mortier of Amsterdam, published and sold playing cards alongside their cartographical inventory. While some had geographical themes, such as Charles Hodges’ famously beautiful deck in which each suit represented a continent, their court cards showing images of native rulers and their pip cards presenting national maps of important countries, a huge range of classic and contemporary motifs are preserved on playing cards. In 1720, mapseller Thomas Bowles published a deck (Item 5) satirizing the “Bubble” schemes that had lately conned money out of eager investors, following the pattern of the notorious South Sea Bubble. Many fraudulent schemes are cruelly illustrated and then reamed in rhyme, including an ‘Office for cureing the Grand Pox or Clap’ on the Three of Diamonds, and an advertisement for ‘Bleeching of Hair’ on the Ten of Clubs.

Many of the earliest printed commercial playing cards were also produced by mapmakers, and some even bore cartographical designs. The card, which shares its name with the word for map in several languages (carte, Karte), has also been ubiquitous across time and space; played by nomads and emperors, parlour maids and Lords, the deck represents a shared pastime that connects all levels of society across the ages.

From the sixteenth century onwards, mapsellers such as John Seller, Richard Blome and Thomas Bowles of London, Pieter Schenck of Leipzig, and Pieter Mortier of Amsterdam, published and sold playing cards alongside their cartographical inventory. While some had geographical themes, such as Charles Hodges’ famously beautiful deck in which each suit represented a continent, their court cards showing images of native rulers and their pip cards presenting national maps of important countries, a huge range of classic and contemporary motifs are preserved on playing cards. In 1720, mapseller Thomas Bowles published a deck (Item 5) satirizing the “Bubble” schemes that had lately conned money out of eager investors, following the pattern of the notorious South Sea Bubble. Many fraudulent schemes are cruelly illustrated and then reamed in rhyme, including an ‘Office for cureing the Grand Pox or Clap’ on the Three of Diamonds, and an advertisement for ‘Bleeching of Hair’ on the Ten of Clubs.

In some cases, the travelling theme blended into the world of fantasy, as in William Darton’s ‘A Voyage of Discovery; or, the Five Navigators’ (Item 7), in which players had to navigate a fictional archipelago, beginning at “Mermaids Rock”, battling pirates, rescuing turtles and bartering for gold dust, all while trying to be the first to reach the ‘Out’ square. On the whole, however, game maps depicted real life places, and it has even been suggested that playing them simulated the experience of the Grand Tour, when wealthy young men would take a trip around the world to supplement their education and social status. Indeed in certain board games the player was referred to as a traveller, such as John Wallis’ Scottish game map of 1792 (Item 6), where the final destination was Edinburgh: “the capital city of all Scotland, where the traveller, having now finished his journey, may congratulate himself on having won the game, and may now view every thing curious without paying for it”.

In some cases, the travelling theme blended into the world of fantasy, as in William Darton’s ‘A Voyage of Discovery; or, the Five Navigators’ (Item 7), in which players had to navigate a fictional archipelago, beginning at “Mermaids Rock”, battling pirates, rescuing turtles and bartering for gold dust, all while trying to be the first to reach the ‘Out’ square. On the whole, however, game maps depicted real life places, and it has even been suggested that playing them simulated the experience of the Grand Tour, when wealthy young men would take a trip around the world to supplement their education and social status. Indeed in certain board games the player was referred to as a traveller, such as John Wallis’ Scottish game map of 1792 (Item 6), where the final destination was Edinburgh: “the capital city of all Scotland, where the traveller, having now finished his journey, may congratulate himself on having won the game, and may now view every thing curious without paying for it”.

The earliest example of an American game map is the Lockwoods' 'Your Traveller's Tour Through The United States’ (Item 8) published in 1822, which extends from the Eastern Seaboard, to the newly incorporated states of Missouri, Maine, and Arkansas, with each town on the game numbered from 1 (Washington) to 139 (New Orleans). A key below the map provides a brief description of each town, together with the population of major conurbations. The game was played with counters and the use of a totem (numbered from 1-8) which was spun. Players were required to name the town on which they had landed, and if they were playing the harder version of the game to name the town’s population, the winner being the person to reach New Orleans first. In 2000, the game appeared on the Library of Congress' "wish list" according to their magazine, Civilization.

The earliest example of an American game map is the Lockwoods' 'Your Traveller's Tour Through The United States’ (Item 8) published in 1822, which extends from the Eastern Seaboard, to the newly incorporated states of Missouri, Maine, and Arkansas, with each town on the game numbered from 1 (Washington) to 139 (New Orleans). A key below the map provides a brief description of each town, together with the population of major conurbations. The game was played with counters and the use of a totem (numbered from 1-8) which was spun. Players were required to name the town on which they had landed, and if they were playing the harder version of the game to name the town’s population, the winner being the person to reach New Orleans first. In 2000, the game appeared on the Library of Congress' "wish list" according to their magazine, Civilization.

Wallis’ oeuvre of game maps covered the entire world: ‘Wallis’s New Game, Exhibiting a Voyage round The World’ (1823) was played on a double-hemisphere world map; ‘Wallis’s New Game of Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (1844) took players on a tour across Latin America; ‘European Travellers, an Instructive Game’ (1845) contained details about Europe’s cultures, industries, topography, and natural history, from bull fighting in Spain to Russians travelling by troika.

Like many other board games from this period, Wallis’ game maps often reflect the European imperialist expansion occurring at the time. ‘Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (Item 10), for example, starts at Demarara, one of the three colonies that made up British Guiana. The intrepid traveller is welcomed by the local plantation owner. He offers the player a tour of this estate where he employs “about two hundred negroes, who were formerly slaves, but I now pay them a regular wage; and find I am a gainer from the abolition of the old system”. Two native Indians are the venturer’s guides and by the use of their deadly blowpipes and arrows provide him with “feathered game, venison, and wild pork, or beef” and defend him from the “treacherous Couguar or more ferocious and powerful Jaguar”.

Wallis’ oeuvre of game maps covered the entire world: ‘Wallis’s New Game, Exhibiting a Voyage round The World’ (1823) was played on a double-hemisphere world map; ‘Wallis’s New Game of Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (1844) took players on a tour across Latin America; ‘European Travellers, an Instructive Game’ (1845) contained details about Europe’s cultures, industries, topography, and natural history, from bull fighting in Spain to Russians travelling by troika.

Like many other board games from this period, Wallis’ game maps often reflect the European imperialist expansion occurring at the time. ‘Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (Item 10), for example, starts at Demarara, one of the three colonies that made up British Guiana. The intrepid traveller is welcomed by the local plantation owner. He offers the player a tour of this estate where he employs “about two hundred negroes, who were formerly slaves, but I now pay them a regular wage; and find I am a gainer from the abolition of the old system”. Two native Indians are the venturer’s guides and by the use of their deadly blowpipes and arrows provide him with “feathered game, venison, and wild pork, or beef” and defend him from the “treacherous Couguar or more ferocious and powerful Jaguar”.

New game maps also appeared in the twentieth century, and indeed continue to be produced today. A key example which reflectsthe culture in which it was made is ‘SCAM: The Game of International Dope Smuggling’ (Item 11) produced in 1971, the same year as President Nixon launched his war on drugs. The rules state:

“Generally Scam goes like this: you begin on the drop out of college square and keep moving around the Ave until you have collected enough money and Connections to get off the Ave. You then work The County and New York until you get enough money to put together a smuggling Scam. That involves Flying to Mexico, Afghanistan or South America, buying dope, smuggling back to the States, and selling in New York (where there’s more money) or in the County (where there’s less Paranoia). To win the game you have to make One Million Dollars. If any of the following rules seem vague, unclear or stupid, feel free to change them to suit yourself.”

New game maps also appeared in the twentieth century, and indeed continue to be produced today. A key example which reflectsthe culture in which it was made is ‘SCAM: The Game of International Dope Smuggling’ (Item 11) produced in 1971, the same year as President Nixon launched his war on drugs. The rules state:

“Generally Scam goes like this: you begin on the drop out of college square and keep moving around the Ave until you have collected enough money and Connections to get off the Ave. You then work The County and New York until you get enough money to put together a smuggling Scam. That involves Flying to Mexico, Afghanistan or South America, buying dope, smuggling back to the States, and selling in New York (where there’s more money) or in the County (where there’s less Paranoia). To win the game you have to make One Million Dollars. If any of the following rules seem vague, unclear or stupid, feel free to change them to suit yourself.”

In fact, the first jigsaws were created from dissected maps which had to be rearranged by the player to form the world, continent or country shown. Their invention has commonly been attributed to John Spilsbury, a British cartographer, engraver and map-seller who affixed maps to a wooden board and carved out each country (Item 1). Earlier references, however, suggest that these sorts of geographical games were already being made by a Madame de Beaumont in the mid-seventeenth century.

Both Beaumont and Spilsbury’s sets were luxurious commodities and thus popular among the elite, for whom such items became symbols of status. In Jane Austen’s 1814 novel ‘Mansfield Park’, for example, the poor protagonist is mocked by her wealthy cousins because she “cannot put the map of Europe together”. The growth of mass education and reduction in printing costs during the nineteenth century, however, meant that these sorts of educational materials became more commercially available and accessible to a wider range of children. Spilsbury’s puzzles, which are described in Mortimer’s Universal Director for 1763 as tools ‘to facilitate the Teaching of Geography’, present a wealth of geographical information, including important cities, rivers and bodies of water, which would certainly have helped augment any child’s knowledge of the world.

In fact, the first jigsaws were created from dissected maps which had to be rearranged by the player to form the world, continent or country shown. Their invention has commonly been attributed to John Spilsbury, a British cartographer, engraver and map-seller who affixed maps to a wooden board and carved out each country (Item 1). Earlier references, however, suggest that these sorts of geographical games were already being made by a Madame de Beaumont in the mid-seventeenth century.

Both Beaumont and Spilsbury’s sets were luxurious commodities and thus popular among the elite, for whom such items became symbols of status. In Jane Austen’s 1814 novel ‘Mansfield Park’, for example, the poor protagonist is mocked by her wealthy cousins because she “cannot put the map of Europe together”. The growth of mass education and reduction in printing costs during the nineteenth century, however, meant that these sorts of educational materials became more commercially available and accessible to a wider range of children. Spilsbury’s puzzles, which are described in Mortimer’s Universal Director for 1763 as tools ‘to facilitate the Teaching of Geography’, present a wealth of geographical information, including important cities, rivers and bodies of water, which would certainly have helped augment any child’s knowledge of the world.

Some publishers took cartographical puzzles to the next level by creating 3D jigsaws out of globes. One such puzzle globe (Item 3) was produced in 1867 by Alphonse Giroux, a French artist who had trained under Jacques-Louis David and had later established a paint shop. Displaying cartography from several decades earlier, Giroux’s globe was dissected into eight cross-sections showing continental maps on the upper side and providing illustrated information on the reverse. Each cross-section was itself divided into four or six pieces, which then had to be assembled to form the globe. Similar puzzle globes were being produced in London at the same time, but no doubt because of their technicality and expense, they are much rarer than their two-dimensional counterparts.

Some publishers took cartographical puzzles to the next level by creating 3D jigsaws out of globes. One such puzzle globe (Item 3) was produced in 1867 by Alphonse Giroux, a French artist who had trained under Jacques-Louis David and had later established a paint shop. Displaying cartography from several decades earlier, Giroux’s globe was dissected into eight cross-sections showing continental maps on the upper side and providing illustrated information on the reverse. Each cross-section was itself divided into four or six pieces, which then had to be assembled to form the globe. Similar puzzle globes were being produced in London at the same time, but no doubt because of their technicality and expense, they are much rarer than their two-dimensional counterparts. Many of the earliest printed commercial playing cards were also produced by mapmakers, and some even bore cartographical designs. The card, which shares its name with the word for map in several languages (carte, Karte), has also been ubiquitous across time and space; played by nomads and emperors, parlour maids and Lords, the deck represents a shared pastime that connects all levels of society across the ages.

From the sixteenth century onwards, mapsellers such as John Seller, Richard Blome and Thomas Bowles of London, Pieter Schenck of Leipzig, and Pieter Mortier of Amsterdam, published and sold playing cards alongside their cartographical inventory. While some had geographical themes, such as Charles Hodges’ famously beautiful deck in which each suit represented a continent, their court cards showing images of native rulers and their pip cards presenting national maps of important countries, a huge range of classic and contemporary motifs are preserved on playing cards. In 1720, mapseller Thomas Bowles published a deck (Item 5) satirizing the “Bubble” schemes that had lately conned money out of eager investors, following the pattern of the notorious South Sea Bubble. Many fraudulent schemes are cruelly illustrated and then reamed in rhyme, including an ‘Office for cureing the Grand Pox or Clap’ on the Three of Diamonds, and an advertisement for ‘Bleeching of Hair’ on the Ten of Clubs.

Many of the earliest printed commercial playing cards were also produced by mapmakers, and some even bore cartographical designs. The card, which shares its name with the word for map in several languages (carte, Karte), has also been ubiquitous across time and space; played by nomads and emperors, parlour maids and Lords, the deck represents a shared pastime that connects all levels of society across the ages.

From the sixteenth century onwards, mapsellers such as John Seller, Richard Blome and Thomas Bowles of London, Pieter Schenck of Leipzig, and Pieter Mortier of Amsterdam, published and sold playing cards alongside their cartographical inventory. While some had geographical themes, such as Charles Hodges’ famously beautiful deck in which each suit represented a continent, their court cards showing images of native rulers and their pip cards presenting national maps of important countries, a huge range of classic and contemporary motifs are preserved on playing cards. In 1720, mapseller Thomas Bowles published a deck (Item 5) satirizing the “Bubble” schemes that had lately conned money out of eager investors, following the pattern of the notorious South Sea Bubble. Many fraudulent schemes are cruelly illustrated and then reamed in rhyme, including an ‘Office for cureing the Grand Pox or Clap’ on the Three of Diamonds, and an advertisement for ‘Bleeching of Hair’ on the Ten of Clubs.

The connection between playing cards and maps took on a new form during the Second World War, through a collaboration between The United States Playing Card Company and the British and American intelligence agencies. Maps of secret escape routes were sandwiched inside playing cards that were delivered to prisoners inside enemy camps. When immersed in water, the two paper layers of the card parted to reveal the map within, with which allied prisoners could then plan their escape. The so-called ‘Map Deck’ was held as such a high-security secret that it is not even known how many were produced!

Alongside the jigsaw puzzle and playing cards, mapmakers were also responsible for many of the earliest commercial board games. In the mid-seventeenth century Parisian cartographer Pierre du Val published a children’s game entitled Le jeu du monde, which involved moving counters across a map of various provinces to reach an end-point; there was even geographical information to be read by those awaiting their next turn. This kind of game became rapidly more popular, until it was the standard format for board games of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In some cases, the travelling theme blended into the world of fantasy, as in William Darton’s ‘A Voyage of Discovery; or, the Five Navigators’ (Item 7), in which players had to navigate a fictional archipelago, beginning at “Mermaids Rock”, battling pirates, rescuing turtles and bartering for gold dust, all while trying to be the first to reach the ‘Out’ square. On the whole, however, game maps depicted real life places, and it has even been suggested that playing them simulated the experience of the Grand Tour, when wealthy young men would take a trip around the world to supplement their education and social status. Indeed in certain board games the player was referred to as a traveller, such as John Wallis’ Scottish game map of 1792 (Item 6), where the final destination was Edinburgh: “the capital city of all Scotland, where the traveller, having now finished his journey, may congratulate himself on having won the game, and may now view every thing curious without paying for it”.

In some cases, the travelling theme blended into the world of fantasy, as in William Darton’s ‘A Voyage of Discovery; or, the Five Navigators’ (Item 7), in which players had to navigate a fictional archipelago, beginning at “Mermaids Rock”, battling pirates, rescuing turtles and bartering for gold dust, all while trying to be the first to reach the ‘Out’ square. On the whole, however, game maps depicted real life places, and it has even been suggested that playing them simulated the experience of the Grand Tour, when wealthy young men would take a trip around the world to supplement their education and social status. Indeed in certain board games the player was referred to as a traveller, such as John Wallis’ Scottish game map of 1792 (Item 6), where the final destination was Edinburgh: “the capital city of all Scotland, where the traveller, having now finished his journey, may congratulate himself on having won the game, and may now view every thing curious without paying for it”. The earliest example of an American game map is the Lockwoods' 'Your Traveller's Tour Through The United States’ (Item 8) published in 1822, which extends from the Eastern Seaboard, to the newly incorporated states of Missouri, Maine, and Arkansas, with each town on the game numbered from 1 (Washington) to 139 (New Orleans). A key below the map provides a brief description of each town, together with the population of major conurbations. The game was played with counters and the use of a totem (numbered from 1-8) which was spun. Players were required to name the town on which they had landed, and if they were playing the harder version of the game to name the town’s population, the winner being the person to reach New Orleans first. In 2000, the game appeared on the Library of Congress' "wish list" according to their magazine, Civilization.

The earliest example of an American game map is the Lockwoods' 'Your Traveller's Tour Through The United States’ (Item 8) published in 1822, which extends from the Eastern Seaboard, to the newly incorporated states of Missouri, Maine, and Arkansas, with each town on the game numbered from 1 (Washington) to 139 (New Orleans). A key below the map provides a brief description of each town, together with the population of major conurbations. The game was played with counters and the use of a totem (numbered from 1-8) which was spun. Players were required to name the town on which they had landed, and if they were playing the harder version of the game to name the town’s population, the winner being the person to reach New Orleans first. In 2000, the game appeared on the Library of Congress' "wish list" according to their magazine, Civilization.One of the most prolific game-makers of the nineteenth century was Edward Wallis, who also sold prints from his premises on Skinner Street in London. Like the Lockwoods, Wallis produced a game map of America, the ‘Game of the Star-Spangled Banner’ (Item 9) published in 1842, which was the first board game to feature a complete map of the United States. The game aimed to teach an English audience about America, and some of the descriptions in the rule book must certainly have astounded the young players, with a number of references to slavery including that “the slave-holders of the southern states are extensively supplied from the markets of Virginia, where negroes are reared for the purpose of sale and traffic… the last taint of negro blood subjects an individual to this degraded condition”. Some of the descriptions of American wildlife too, must have been alarming, such as that of the Turkey Buzzard, which “feeds on carrion, and if attempted to be taken, vomits the contents of its stomach in the face of its pursuer, emitting the most intolerable stench”, and the Grizzly Bear: “the largest and fiercest animal on this continent. His very name is dreadful, as his disposition is bloodthirsty”.

Wallis’ oeuvre of game maps covered the entire world: ‘Wallis’s New Game, Exhibiting a Voyage round The World’ (1823) was played on a double-hemisphere world map; ‘Wallis’s New Game of Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (1844) took players on a tour across Latin America; ‘European Travellers, an Instructive Game’ (1845) contained details about Europe’s cultures, industries, topography, and natural history, from bull fighting in Spain to Russians travelling by troika.

Like many other board games from this period, Wallis’ game maps often reflect the European imperialist expansion occurring at the time. ‘Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (Item 10), for example, starts at Demarara, one of the three colonies that made up British Guiana. The intrepid traveller is welcomed by the local plantation owner. He offers the player a tour of this estate where he employs “about two hundred negroes, who were formerly slaves, but I now pay them a regular wage; and find I am a gainer from the abolition of the old system”. Two native Indians are the venturer’s guides and by the use of their deadly blowpipes and arrows provide him with “feathered game, venison, and wild pork, or beef” and defend him from the “treacherous Couguar or more ferocious and powerful Jaguar”.

Wallis’ oeuvre of game maps covered the entire world: ‘Wallis’s New Game, Exhibiting a Voyage round The World’ (1823) was played on a double-hemisphere world map; ‘Wallis’s New Game of Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (1844) took players on a tour across Latin America; ‘European Travellers, an Instructive Game’ (1845) contained details about Europe’s cultures, industries, topography, and natural history, from bull fighting in Spain to Russians travelling by troika.

Like many other board games from this period, Wallis’ game maps often reflect the European imperialist expansion occurring at the time. ‘Wanderers in the Wilderness’ (Item 10), for example, starts at Demarara, one of the three colonies that made up British Guiana. The intrepid traveller is welcomed by the local plantation owner. He offers the player a tour of this estate where he employs “about two hundred negroes, who were formerly slaves, but I now pay them a regular wage; and find I am a gainer from the abolition of the old system”. Two native Indians are the venturer’s guides and by the use of their deadly blowpipes and arrows provide him with “feathered game, venison, and wild pork, or beef” and defend him from the “treacherous Couguar or more ferocious and powerful Jaguar”.

New game maps also appeared in the twentieth century, and indeed continue to be produced today. A key example which reflectsthe culture in which it was made is ‘SCAM: The Game of International Dope Smuggling’ (Item 11) produced in 1971, the same year as President Nixon launched his war on drugs. The rules state:

“Generally Scam goes like this: you begin on the drop out of college square and keep moving around the Ave until you have collected enough money and Connections to get off the Ave. You then work The County and New York until you get enough money to put together a smuggling Scam. That involves Flying to Mexico, Afghanistan or South America, buying dope, smuggling back to the States, and selling in New York (where there’s more money) or in the County (where there’s less Paranoia). To win the game you have to make One Million Dollars. If any of the following rules seem vague, unclear or stupid, feel free to change them to suit yourself.”

New game maps also appeared in the twentieth century, and indeed continue to be produced today. A key example which reflectsthe culture in which it was made is ‘SCAM: The Game of International Dope Smuggling’ (Item 11) produced in 1971, the same year as President Nixon launched his war on drugs. The rules state:

“Generally Scam goes like this: you begin on the drop out of college square and keep moving around the Ave until you have collected enough money and Connections to get off the Ave. You then work The County and New York until you get enough money to put together a smuggling Scam. That involves Flying to Mexico, Afghanistan or South America, buying dope, smuggling back to the States, and selling in New York (where there’s more money) or in the County (where there’s less Paranoia). To win the game you have to make One Million Dollars. If any of the following rules seem vague, unclear or stupid, feel free to change them to suit yourself.”

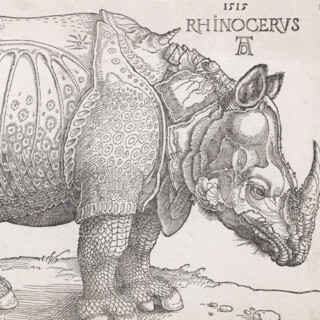

The game features maps of Afghanistan, India, Mexico and South America, with a cameo appearance by Uranus in the upper-left corner, and New York, “The Ave” and “The County” as squared diagrams beneath. Colourful and irreverent, ‘SCAM’ represents the transition of the board game into the modern world, one in which these games, though undoubtedly still popular, have been eclipsed by their digital counterparts. Yet maps continue to play just as important a role in video games, particularly those of real-time strategy and role-playing, in which they are often far more realistic than in earlier games. This is not only thanks to advanced digital graphics, but due to the fact that certain regions or features of the terrain often become visible on a map only when the player has explored them.

Games and maps have an analogous relationship to reality. Both are microcosms, representing the world in a way that allows people to interact with it for utility, pleasure, profit, or necessity. Combined, they become a source of entertainment through which we can enjoy exploring different times, places and lives, from being an international drug smuggler in the 70s to traversing the jungles of nineteenth century South America.