The work that turned Europe Upside Down

Mappa Europae,

Eygentlich für gebildet aussgelegt und beschriebenn.

SKU: 22979

Browse Natural History, Science & Medicine Sale 2026

Tags: 140126, December25, Maastricht 2025, map. surveying, Munster

Type: Rare Books

MÜNSTER, Sebastian

Frankfurt,

Christian Egenolph,

1536.

Quarto (200 by 150mm). Title-page woodcut vignette, two double-page woodcut maps at the rear, one bound upside-down, one full-page map, illustrated profusely throughout with woodcuts, including two surveying instruments hand-coloured in part; modern vellum, title inked to spine, bookbinder's ticket on the front pastedown, top edge dyed blue, some damp stains in margins throughout, small tear to bottom margin at D2-3, not affecting text, small early repairs to heads of both double-page maps.

200 by 150mm. (7.75 by 6 inches).

22979

To scale:

notes:

notes:

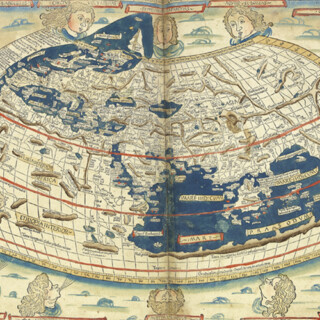

Extremely rare first edition of Münster's first geographical work, including The earliest acquirable map of Europe oriented to the south.

Declared "the later Cosmographia in microcosm" (Karrow), this very early pamphlet is a lay practical guide on map making, reading, and navigation across Europe. It is the first appearance of Münster's 'inverted' map - an innovation so radical that the binder instinctively turned the double-page map of Europe 'the right way up' ...

Declared "the later Cosmographia in microcosm" (Karrow), this very early pamphlet is a lay practical guide on map making, reading, and navigation across Europe. It is the first appearance of Münster's 'inverted' map - an innovation so radical that the binder instinctively turned the double-page map of Europe 'the right way up' ...

Extremely rare first edition of Münster's first geographical work, including The earliest acquirable map of Europe oriented to the south.

Declared "the later Cosmographia in microcosm" (Karrow), this very early pamphlet is a lay practical guide on map making, reading, and navigation across Europe. It is the first appearance of Münster's 'inverted' map - an innovation so radical that the binder instinctively turned the double-page map of Europe 'the right way up' in error. This innovation in orientation was beneficial for both cartographers and travellers, as coastlines and journeys could be plotted simply with a sundial or compass. Such ease of navigation cemented this 'inversion' as the first 'modern' orientation.

Although Erhard Etzlaub, a Nuremberg chronicler, was the first to use this southern orientation in his 1499 map of Rome, it is more likely that Münster took inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller's later 1511 world map - as evidenced by the ten sketches of it found in Münster's schoolbook.

Therefore, whilst not originating from Münster directly, he was the first to map Europe with a southern orientation, and his later adoption of this in the Geographia (1540) and Cosmographia (1544) set a firm cartographical standard.

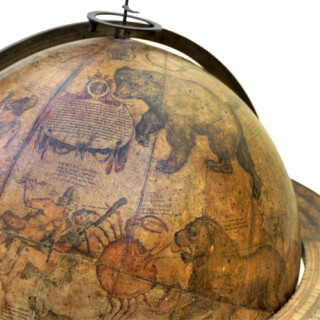

A second striking feature of this sixteenth-century German cartographic style was a focus on involving the audience. Reading maps was recommended in tandem with the use of precision instruments, which is exemplified in the present work by the repeated sundial woodcut. Münster also details how such a sundial can be made and used, providing a cheaper alternative to the magnetic surveying instruments of learned cartographers. Furthermore, Münster instructs readers on: how to determine latitude, distances between cities, navigation by sun compass, and how a reader can create their own map.

By publishing in the vernacular, cutting-edge cartography could be recognised by a lay audience. Mappa Europa was intended as a popular alternative to Münster's earlier Germaniae descriptio (1530), written in academic Latin. "The Mappa should thus be understood as a prospectus designed to encourage general interest in cosmography, no more the domain of a limited number of learned people... but now aimed at the masses and townsfolk" (Burmeister).

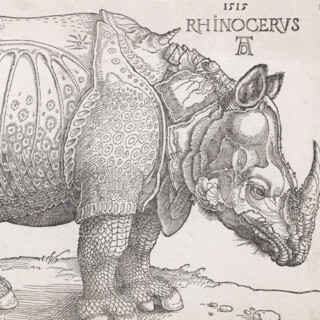

After this practical guidance, Münster describes key cities, states, and countries in Europe. His guide-book style descriptions point towards the development of commercial travel in the sixteenth century; whilst his two regional maps of Heidelberg and Basel were closer to home, Münster includes woodcut vignettes to accompany places as exotic as Tartary and Turkey. Holland is described as having strong men with good manners, who are devout and loyal. England, on the other hand, had beautiful women but a vindictive, superstitious, and cruel people. Münster makes note of which countries contain wolves, poisonous animals, and vineyards, which lends an entertaining insight into the concerns of the Discovery Period.

Rare: we have traced only one North American example of the 1536 edition (NYPL), lacking both double-page maps. Two examples of the second edition are held in Harvard and Yale, although the former lacks the maps. No complete example has come up at auction in the last fifty years.

Declared "the later Cosmographia in microcosm" (Karrow), this very early pamphlet is a lay practical guide on map making, reading, and navigation across Europe. It is the first appearance of Münster's 'inverted' map - an innovation so radical that the binder instinctively turned the double-page map of Europe 'the right way up' in error. This innovation in orientation was beneficial for both cartographers and travellers, as coastlines and journeys could be plotted simply with a sundial or compass. Such ease of navigation cemented this 'inversion' as the first 'modern' orientation.

Although Erhard Etzlaub, a Nuremberg chronicler, was the first to use this southern orientation in his 1499 map of Rome, it is more likely that Münster took inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller's later 1511 world map - as evidenced by the ten sketches of it found in Münster's schoolbook.

Therefore, whilst not originating from Münster directly, he was the first to map Europe with a southern orientation, and his later adoption of this in the Geographia (1540) and Cosmographia (1544) set a firm cartographical standard.

A second striking feature of this sixteenth-century German cartographic style was a focus on involving the audience. Reading maps was recommended in tandem with the use of precision instruments, which is exemplified in the present work by the repeated sundial woodcut. Münster also details how such a sundial can be made and used, providing a cheaper alternative to the magnetic surveying instruments of learned cartographers. Furthermore, Münster instructs readers on: how to determine latitude, distances between cities, navigation by sun compass, and how a reader can create their own map.

By publishing in the vernacular, cutting-edge cartography could be recognised by a lay audience. Mappa Europa was intended as a popular alternative to Münster's earlier Germaniae descriptio (1530), written in academic Latin. "The Mappa should thus be understood as a prospectus designed to encourage general interest in cosmography, no more the domain of a limited number of learned people... but now aimed at the masses and townsfolk" (Burmeister).

After this practical guidance, Münster describes key cities, states, and countries in Europe. His guide-book style descriptions point towards the development of commercial travel in the sixteenth century; whilst his two regional maps of Heidelberg and Basel were closer to home, Münster includes woodcut vignettes to accompany places as exotic as Tartary and Turkey. Holland is described as having strong men with good manners, who are devout and loyal. England, on the other hand, had beautiful women but a vindictive, superstitious, and cruel people. Münster makes note of which countries contain wolves, poisonous animals, and vineyards, which lends an entertaining insight into the concerns of the Discovery Period.

Rare: we have traced only one North American example of the 1536 edition (NYPL), lacking both double-page maps. Two examples of the second edition are held in Harvard and Yale, although the former lacks the maps. No complete example has come up at auction in the last fifty years.

bibliography:

bibliography:

Bagrow, 'Carta Itineraria Europe Martini Ilacomili, 1511', Imago Mundi XI, pp149-50; Hantzsch, pp39-41, 75-76, 148 (note 63); I Graesse IV, 622;Karrow, Mapmakers of the Sixteenth Centuries, 58/P; Woodward, The History of Cartography, p1211; VD16 M6677.

provenance:

provenance: