Carceri d’Invenzione.

- 作者: PIRANESI, G[iovanni] Battista

- 出版地: [Rome]

- 发布日期: [1778-1799].

- 物理描述: 16 etchings, fleur-de-lys with crown and Bracciano watermarks (Robison 58 and 59). A full condition report is available on request.

- 方面: (each approximately) (plate) 545 by 415mm. (21.5 by 16.25 inches), (sheet) 750 by 565mm. (29.5 by 22.25 inches).

- 库存参考: 22618

笔记

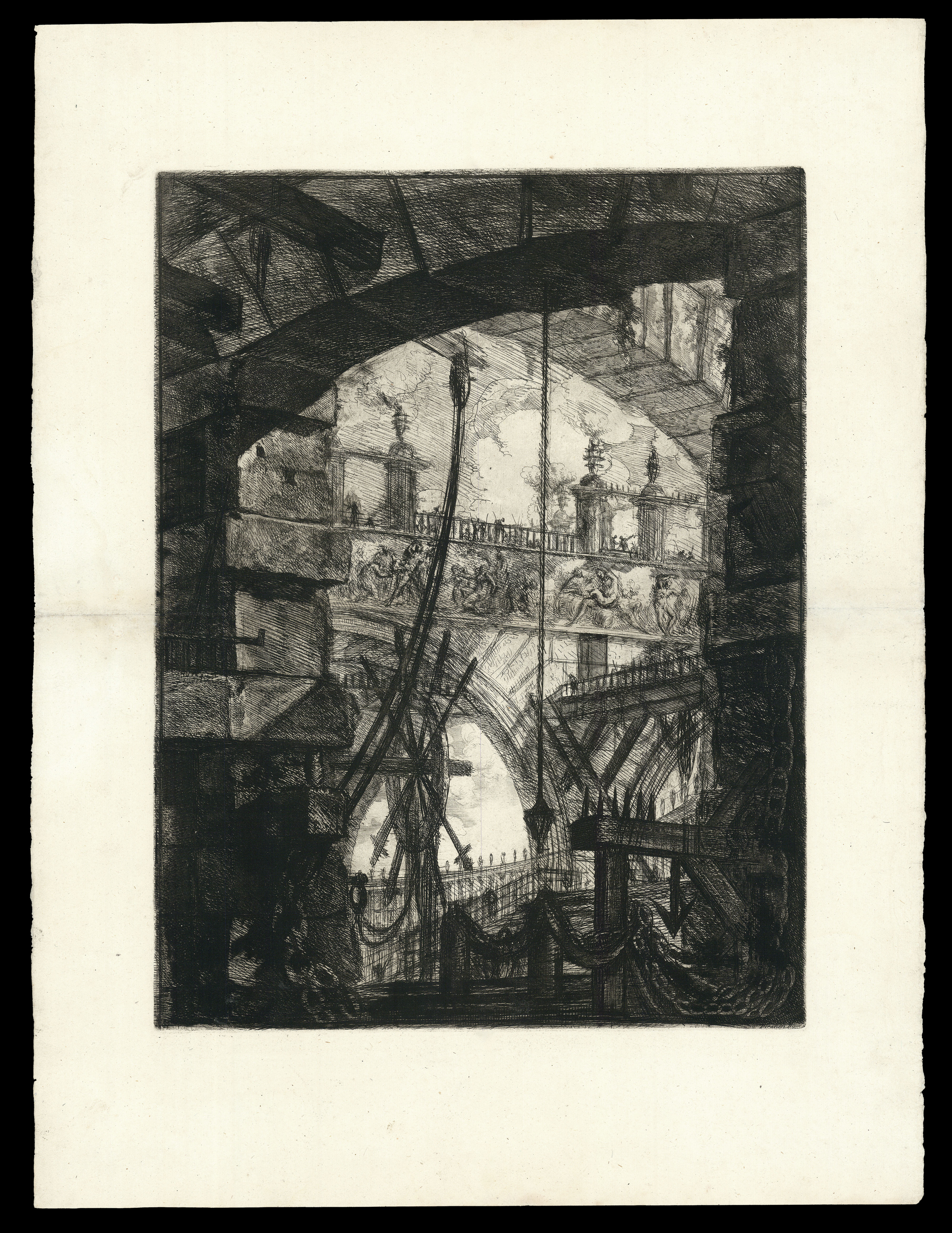

A fine set of the ‘Carceri d’Invenzione’, the exquisitely haunting series of etchings of imagined prisons by one of the greatest printmakers of the eighteenth century, Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

The ‘Carceri’ were first published by Bouchard, between 1749 and 1750, as the ‘Invenzioni Capric di Carceri’. This first edition comprised 14 plates that depict looming, cavernous architectural forms, which, while monumental, are drawn with such lightness of etching that they bear little resemblance to their titular ‘prisons’.

The plates were subsequently revised and republished by Piranesi himself in 1761, now titled the ‘Carceri d’Invenzione’. This second edition includes two additional plates (plate II, ‘The Man on the Rack’, and plate V, ‘The Lion Bas-Reliefs’), taking the total to 16, and shows significant reworking, assuming a far more sinister, and prison-like, character. With the plates darkened and more densely cross-hatched, and with an abundance of contraptions, pulleys, rings, iron spikes, beams, and ladders added, the atmosphere becomes oppressive, claustrophobic, and menacing – a threat that is made explicit in ‘The Man on the Rack’ (plate II), which depicts a visceral scene of human torture.

Four further editions followed, the present set being an example of the third edition, published between 1778 and 1799, with fleur-de-lys and “Bracciano” watermarks (Robison 58 and 59), denoting an early issue.

“Lex Romana”, stairways to nowhere, and opium-eaters

Piranesi’s imagined ‘Carceri’ may not reflect the prisons of his contemporary Italy, but they are deeply embroiled in contemporary debate – albeit one that looked distinctly towards the past. The mid-eighteenth century saw the emergence of the “Greco-Roman Controversy”, with Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) arguing for the pre-eminence of ancient Greece, and Piranesi a principal advocate for the superiority of ancient Rome. Piranesi’s championing of Rome over Greece is reflected by the additions that he makes to the second (1761) edition of the ‘Carceri’. To the revised ‘The Pier with Chains’ (plate XVI), for example, Piranesi added three Latin inscriptions, each of which allude to an episode in Livy’s ‘History of Rome’ (among them, the establishment of the first prison by King Ancus Marcius and the solemn law of the duumvirs), designed to reflect positively on the severe, yet just, “Lex Romana”. ‘The Man on the Rack’ (plate II), by contrast, can be read as a statement on the decline of Roman law under the rule of the philhellene Emperor Nero, the names inscribed below the portrait reliefs those of men whom he unjustly punished, as recorded by Tacitus.

Yet, while Piranesi’s ‘Carceri’ might take on a historical dimension, looking to ancient Rome, they remain, at their core, feats of the imagination. Peppered with architectural ambiguities, stairs that lead to nowhere, zigzagging bridges, one can understand the influence of Piranesi on the artist Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972), who played with labyrinthine, infinite, impossible space. Indeed, for English writer, essayist, and literary critic Thomas de Quincey (1785-1859), the ‘Carceri’ become comparable to the stimulation of his own imagination by the consumption of opium, as he writes in ‘Confessions of an English Opium-Eater’:

“Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s Antiquities of Rome, Mr Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist, called his ‘Dreams’, and which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever. Some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr Coleridge’s account) represented vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, &c. &c., expressive of enormous power put forth and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further and you perceive it come to a sudden and abrupt termination without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him who had reached the extremity except into the depths below. Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi, you suppose at least that his labours must in some way terminate here. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived, but this time standing on the very brink of the abyss. Again elevate your eye, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld, and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labours; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall. With the same power of endless growth and self-reproduction did my architecture proceed in dreams” (De Quincey).

The artist

Architect, draftsman, scholar, archaeologist, and designer, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) was born in Venice, the son of a stonemason. Pursuing an early ambition to become an architect, he was apprenticed to his uncle Matteo Lucchesi, a prominent architect and hydraulic engineer, and then to the Palladian architect Giovanni Scalfurotto. He later studied etching and perspective composition in the workshop of Carlo Zucchi. In 1740, he travelled to Rome, where he studied set design with Domenico and Giuseppe Valeriani and engraving with Giuseppe Vasi. He would go on to produce 1,000 etched plates over the course of his career, be elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, include Pope Clement XIII among his patrons, and become a key influence in the development of neoclassicism.

List of plates

Plate I: ‘Title Page’ (sheet: 735 by 565mm; plate: 545 by 415mm)

Plate II: ‘The Man on the Rack’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 560 by 420mm)

Plate III: ‘The Round Tower’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 550 by 415mm)

Plate IV: ‘The Grand Piazza’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 545 by 415mm)

Plate V: ‘The Lion Bas-Reliefs’ (sheet: 750 by 560mm; plate: 565 by 415mm)

Plate VI: ‘The Smoking Fire’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 545 by 400mm)

Plate VII: ‘The Drawbridge’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 555 by 410mm)

Plate VIII: ‘The Staircase with Trophies’ (sheet: 750 by 565mm; plate: 545 by 400mm)

Plate IX: ‘The Giant Wheel’ (sheet: 750 by 560mm; plate: 545 by 410 mm)

Plate X: ‘Prisoners on a Projecting Platform’ (sheet: 560 by 750mm; plate: 415 by 545mm)

Plate XI: ‘The Arch with a Shell Ornament’ (sheet: 565 by 750mm; plate: 410 by 545mm)

Plate XII: ‘The Sawhorse’ (sheet: 560 by 750mm; plate: 415 by 555mm)

Plate XIII: ‘The Well’ (sheet: 560 by 750mm; plate: 410 by 550mm)

Plate XIV: ‘The Gothic Arch’ (sheet: 565 by 750mm; plate: 415 by 545mm)

Plate XV: ‘The Pier with a Lamp’ (sheet: 560 by 745mm; plate: 410 by 545mm)

Plate XVI: ‘The Pier with Chains’ (sheet: 555 by 745mm; plate: 405 by 550mm)

地图

地图  地图集

地图集  珍本

珍本  版画

版画  天文仪器

天文仪器